Had he lived, he would have been eighty-four years old today.

My grandfather, whom I never knew and neither did my mother, enlisted in the army and volunteered southward to Quang Tri province, ground zero in the civil war’s bloodiest year yet, 1968. He, among many rural countryside men, left behind their wives, children, even new-born babies they would never have a chance to reunite with, to fight the “just” war in the hope for a reunified nation.

Since a little child, listening to tales about grandpa told by my grandma and my mom, I often visualized the fierce battles in which heroic men and women fought the enemies on the front lines. I was a poor kid with rich imagination, way before the Hollywood blockbusters and war movies invaded our culture. Somehow, my grandfather was and is always an enigmatic figure in my life. Somehow, I feel he lives through me. And why not? I am descendent of him and my grandmother, a fierce single mom raising four young daughters into strong, independent women.

When I was in grade nine, the literature course had plenty of war-time poems about patriotism and soldiers’ life. To some sensitive critics, that sounds like programed indoctrination. What country doesn’t do that anyway? To me back then, the poems were just beautiful: the wording, the rhythm in alliteration, the graphic world they unfold. One such poem, named “The Poem about the Glassless-truck Battalion” by Pham Tien Duat, immortalized the perseverance and optimism of our Vietnamese soldiers who operated wheel vehicles to transport personnel and cargo to battlefields. The vehicles were “glassless” as a result of heavy bomb blast waves, another brutal truth of the war against the Americans.

For homework assignment, my literature teacher, a stout lady with sweet gentle voice, decided to veer off the beaten road of analysis essays. “Let’s pretend you chanced to meet the veterans of the “glassless” battalion,” she told the class, “what would that be like? Let’s tell that story.”

Little would I know a week later, finding myself in disbelief, I received the highest grade for my writing. “You understand the prompt. The writing is very creative and rich in depth;” she commented, “the flow of narration is harmonized with description and expressiveness.” As she stood in front of the class, my teacher read aloud my writing piece to the whole class; her eyes a little wet, a mixture of happiness and pride in her student, something we teenage students rarely saw from a teacher who always demanded the best.

My writing assignment was a personal success, not because it enraptured the audience, but because it sparked in me, a curious 15-year-old, a nascent belief that I could accomplish something meaningful, that I can touch someone’s heart as long as I pour my heart into it. It was such a thrill to an insecure teenager, who secretly craved affirmation but never the limelight, to know that his words had power to move people.

As I continued to high school, the literature curriculum was heavily prose-analysis and rote memorization. Creative writing, deprived of enough oxygen, turned into embers hibernating underground, but it never perished. The entirety of my writing assignment (in 2006), I dare translate here, hopefully will reach you whose faith in literature and writing never ceases existing. Now let’s buckle your seat belt and start our journey.

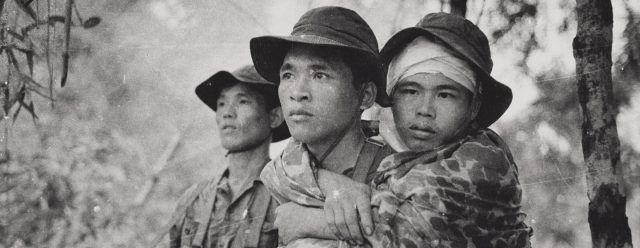

- Vietnamese soldiers during the Vietnam War. Photo credit by PBS

—————————————-

The first ray of light shone through the window shades as I woke in my grandpa’s calling. A new day has come. Today my grandpa and I would be returning to his battlefield where he had so many memories with his comrades and the war itself.

Not allowing the sweltering summer heat take its grip on us, we hopped on the train travelling from Hanoi to the historic central coastland. By noon when the sun was high above our heads, I felt a pang of unfamiliarity while we trekked on the lonesome, imposing Truong Son mountains. In front of me stood mountain peaks that shot through the sky and evergreen giant trees measuring a few hundred feet in height. How much Truong Son mountains have changed over the years: a slightly aloof peaceful scenery; the red-soiled trails, once haunted with smoke and dirt, now were groomed into the interprovincial route, the lifeblood of central Vietnam.

My grandpa walked with me along the route as we saw a small town and little huts of ethnic minority peoples. We came across a troop of people getting off a minibus; they aged around fifty and sixty years old, wearing military uniforms with medals on their chests. Without saying anything, grandpa gravitated toward the crowd; his eyes had two trails of tears, quite emotional. I realized that these men were my grandpa’s former comrades, whom I once met. They hugged tightly, patted one another’s shoulders, shook hands and exploded in joy of laughter.

We stopped by an ethnic village inhabited by hospitable locals. During the war these local people became our trusted allies. When grandpa approached and greeted him, the village chief knew in an instant and was blissful.

Sat next to grandpa inside the village communal house, the welcoming place for honored guests, I didn’t miss the men’s conversation. My grandfather was a driver tasked with transportation during the war. He often mentioned old heroic times, but today he was particularly passionate. I quickly immersed in the majestic scenes emerging from his tales, a narration so emotional, proud and expressive. From the poor country village, like many of his poor countrymen, rich in love and pride for motherland, grandpa enlisted in the army, believing that his country’s survival depended on him; his heart believed in a victorious end.

Endowed with leadership and excellent driving skills, grandpa was stationed with the truck battalion. Due to the brutality of the bombing, the trucks were no longer intact; they rusted into hoodless vehicles, lacking glass and signal lighting. Day in and day out, they were familiar to grandpa. He knew that war won’t keep anything in perfect condition, but he still took comfort in driving the trucks, his head held high. Truong Son mountains could be sunny on one side and rainy on the other; Truong Son dirt would coat evergreen leaves a scarlet tint. All seemed to trouble the drivers of glassless trucks; their eyes sore with dirt; their faces smeared with mud, they laughed; showers soaked their shirts but wind will dry them all, they laughed. The higher they rose above the harshness of nature, the closer their companionship forged. The men encouraged one another and themselves, sacrificing one’s for the country’s sake.

Grandpa said that the Americans went any length to curb the north-south sustenance line. They bomb-raided every inch of the land, destroying every bridge, setting landmines and time bombs. It would take just a millisecond of carelessness and death would claim his toll. Despite all the danger and difficulties, grandpa kept his optimism; still he extended a handshake through the glassless side door. The handshakes seemed to pass vitality so that he forged on, though the soldier knew better than anyone that his fate depended on good luck treading roads plagued with unexploded bombs.

I asked grandpa if he had any minutes of rest. He chuckled and said there were few but short minutes. Battlefields had their sense of urgency; everyone wanted to try their best to liberate the south and unify the divided country. Nonetheless, grandpa could still make fire and cook – the simplistic dinners lacking in nutrients but abundant in friendship. I asked him whether lighting a fire would equal signaling to the enemies. The men around me were amused, telling me that “Hoang Cam stove”, a Vietnamese military invention, helped [diffuse the smoke and thus] reduce our trace from the enemy’s radar. They pointed toward a little stove at one of the room’s corners. I marveled at the genius of our people.

Grandpa mentioned the time for vehicle maintenance in which men would burst out laughing at bygone windshield glass. The men reminisced those nights circling the camp fire, playing the guitars, sharing meals and even chopsticks, just like a family. By dawn the next day, they would be cutting through the dense forests and treacherous waters. Vast forests with lurking dangers could scare grandpa no more as he had friends by his side. Everyone, all hands on deck: young female volunteers shouldered ammunition cargos as if having extraordinary strength; foot soldiers trekked formidable distance; the landmine-detecting women troop always gave bright fearless smiles; canon-hauling troops would work tirelessly without rest; the guerrillas knew their skills and risk-taking propensity. All of those people worked selflessly, which meant that nothing could prevent my grandpa the truck driver from sacrificing himself for the country’s independence.

Life with tribulations wasn’t at all tedious. No matter what, he had his fellow soldiers walked, always walked and would walk in unison with the battalion, like a close-knit family. Grandpa often said, “When you stand shoulder to shoulder with your fellows, there is no backing down; when you feel lonely you have friends; when you’re down you have friends to comfort; when you’re in pain your friends share the pain; when you’re victorious everyone shares the joy.”

The village chief drew a long breathing in at his tobacco bamboo tube, gently telling me that, back in the day, my grandpa fought fiercely. It was his glassless truck that saved the chief from his near-death experience. My grandpa was not a tank-driver, the kind of indestructible steel machine. Instead, he was only a truck driver, glassless-truck driver. His only fear was none but being unable to free the south. He admired his fellows from the messenger boys to commanders-in-chief. All of them pass on the will to strive and compete for victories. It was his tireless efforts that grandpa scored successes one after another, eventually being awarded the highest medal of labor, a deserved credit given by the country.

So he marched on with the heart full of love for life, for his country and fellow peoples, and for justice. Grandpa was the flame that honor justice, warm light in the darkness of war. He never backed down because that heart is tied toward justice, the southern land, and the glassless trucks.

Memories of my visit to Truong Son mountains shall never fade in my heart. My gratitude to you, my grandpa, and to numerous nameless soldiers who laid their bodies down for this country to have freedom. Thank you for teaching me to love life, to have pride in our people, to learn to live and love people, and to never forget that I am a grandson of a fearless Truong Son glassless-truck driver!

2006

The End

—————————————-

Often I wonder how the lives of those valiant soldiers – Vietnamese, American, Russian, Korean or any nationalities involved, no matter what political beliefs they held – would look like had they survived the war and returned home. Survival might not be all happy – in fact, it might be worse than passing, given the traumatic wounds after so many atrocities they witnessed or participated in. I think that Lincoln said it all, “a house divided against itself cannot stand.” It’s no point crying at the past or demanding from the future. I just know that my grandpa lives in my imagination as a hero, and that in heaven he’s always smiling at me, encouraging me to bring my gifts of imagination and writing to bridge the gap of memory, OUR gap of memory, every generation touched by wars. It’s a wonderful way to serve one another. That makes all the difference.